Recording:

John Eliot Gardiner, Monteverdi Choir/English Baroque Soloists; Malin Hartelius,

soprano; James Gilchrist, tenor; Peter Harvey, bass

Finding

subjects to write about has not been a problem on this project: the challenge,

as this week, is to decide what topics to focus on to keep the notes at a

manageable length. For example, who could resist trying to track down some

facts about someone named Cyriakus Schneegass? That gentleman was a 16th-century

German theologian, writer, composer and music theorist who penned the words

associated (in the context of this cantata) with the chorale tune which

provides one line of the “tour de force of contrapuntal mastery” in the “opulent”

opening chorus (John Eliot Gardiner’s description).

Following four measures instrumentally

depicting the labored groaning of someone sore in body and spirit, the altos enter

to initiate the fugue on the first half of the verse from Psalm 38. There are

no long melismatic passages in this chorus, but Bach’s complex structure creates

extended phrases that require staggered breathing and careful balancing (the

alto part is easily covered up by the other voices and benefits from the

addition of male altos – or tenors, if they can be spared). This is a difficult movement and not a good

choice to extract since it relies on the remainder of the cantata to balance

its subject matter and musical content.

This movement is also the subject of a

lengthy analysis in 19th-century British writer, composer and music

theorist Ebenezer Prout’s Fugal Analysis

(1892). Prout chose the chorus as his final textbook example because

“In the same movement we find

here combined an example of close fugue, double fugue with a separate

exposition of each subject, fugue on a chorale, and accompanied fugue. Here,

therefore, we have within the limits of 74 bars, a résumé of nearly the entire contents

of this volume.”

Poor

Prout probably spent more time analyzing this chorus than J.S. needed to

compose it, and unfortunately, although he was a capable educator, Prout’s own

choral works show a conspicuous lack of any comparable inspiration.

One of my

preconceptions entering into the project was that Bach wrote music and then fit

text into it – than which nothing could be further from the truth. Every

musical idea in the cantatas flows from the contemplation of the text – or more

accurately the ideas behind the texts. While the text of BWV 25 may seem overblown

to modern readers, it would have sounded quite appropriate to its intended

audience. For example, the German translation of the psalm verse includes the

word Dräuen (threats), as opposed to

the KJV’s “anger”. A God who is not just angry, but actively threatens the

sinner with terrible punishments, aligns with the doctrine of original sin that

underpins the cantata.

Excerpt from Psalm 38 in the German Lutheran Psalter

That doctrine, accepted by each congregant in the

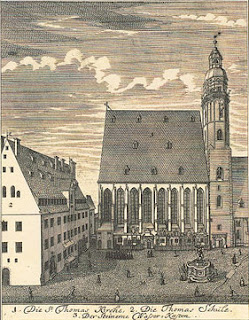

Thomaskirche, is elaborated by the tenor secco

recitative, the words of which were described as going “beyond all endurable

limits of tastelessness” by Albert Schweitzer. It’s difficult to understand

this comment, given that Schweitzer must have been familiar with the historical

context of the cantatas as well as the prolific (and mostly pedestrian) verse

writing occurring throughout the century leading up to Bach that provided the

bulk of the master’s cantata material. Some of the BWV 25 words are found in

Johann Jakob Rambach’s Geistliche Poesien

(1720) but this is not a verbatim source – the unknown poet appears to have

improved it. More colorful bits of the recit, for example, Der andre lieget krank/An eigner Ehre hässlichem Gestank – a line “sanitized”

in the 19th-century piano-vocal score – trace directly back to Psalm

38 (KJV 38:5 “My wounds stink and are corrupt because of my foolishness”). For

a composer creating a dramatic arc, only with the acknowledgment of the fundamentally

miserable condition of man does a path to salvation become plausible and

necessary. Eric Chafe notes that this recitative is “one of the most

harmonically complex in the Bach cantatas”.

Excerpt from Rambach's Geistliche Poesien (1720)

The bass aria (its text also

whitewashed in the vocal score) introduces the metaphor of Jesus as the healing

physician (Arzt) who can provide the Seelenkur. The difficulty of this aria

lies more in interpretation than vocal technique, and it is probably best left to

study when you are hired to sing the cantata. The soprano aria, however, is suitable

for either recital or church use by a high soprano. Following a recitative where

the patient’s willingness to turn away from sin and be “cured” is mirrored by

the musical turn from A minor into C major, this gentle minuet offers up one’s schlechten (I translate this as simple,

or lowly) Liedern with the lovely

promise that these will be perfected Wenn

ich dort im höhern Chor/Werde mit den Engeln singen.

The comparison of the

state of humanity to the ailing populace of a hospital naturally led to the

question of what “hospital” meant in Bach’s time. The early 18th-century

was a time of transition between convent care and the modern concept of a

secular hospital. The Charité had recently (1710) been established in Berlin as

a quarantine facility for bubonic plague victims, but within several years it contained

a medical school and operating theater. The state of these facilities was

primitive, and probably frightening to people accustomed to relying on traditional

religious organizations to provide medical care – a hospital was definitely a place to

be avoided since you stood a good chance of dying if you went there. While the

many strands of medical knowledge were on the cusp of coalescing to become a

science, in the meantime, anyone could label themselves a “doctor” regardless

of educational background. Travelling “physicians” could be quite successful, effecting

cures and then exiting before any bad consequences could definitely be attributed

to them: an example being the “celebrity” eye doctor John Taylor who operated

on Bach, which operation is suspected of contributing to the master’s demise several

months later.

Although this has nothing specifically to do with the cantatas, last week the New York Times

ran an update on the progress of Voyager 1, the space probe launched in 1977

that carries the “Golden Record” - the sounds of Earth hopefully sent as a greeting to some distant civilization. Although not quite providing “Bach, all of

Bach, streamed out into space, over and over again” – Lewis Thomas’ famous

statement that although by doing so the human race would be “bragging”, it was still the best conceivable way to represent humanity – the record does

contain three selections of Bach’s music. All are instrumental – the

only classical vocal or choral excerpt is Der

Hölle Rache from Die Zauberflöte,

sort of an odd choice but no one asked for my input. At the time Voyager 1 left

earth, I was still in high school with all my mistakes in front of me, and my

exposure to Bach was limited to an unfortunate experience trying to teach

myself a 2-part invention.

Three centuries ago as Bach pursued his vocation in Weimar, did he ever look up at the clear night sky and wonder what was out there? The stars were no longer a mythical realm but something to be pursued, studied, and understood: Copernicus and Kepler had formulated the basic shape and motion of the solar system well before the master's lifetime. So perhaps he did wonder if the music he so devoutly offered up could be heard by a celestial audience. Now in a remarkable and historic achievement of technology and optimism, Voyager 1 is about to exit the solar system, to take Bach’s

music to the heavens.

Voyager 1 Golden Record