Recording:

Rudolf Lutz, Chor/Orchester der J.S. Bach-Stiftung; Markus Forster, altus; Johannes Kaleschke, tenor; Ekkehard Abele, bass

The

performing arts are unique from most professions in that in order to get a job,

you usually have to demonstrate that you can actually do the job through an

audition. This as opposed to something like engineering, where you produce a

resume, buy a nice suit, do an interview, and providing you show a few signs of

intelligent life, you get a job offer to do – something that you will have to

learn how to do on the job. However, one thing that is common to all careers is

that for the best jobs, there is not only a highly-competitive field of capable

applicants, but there are political favorites and those with an inside track.

J.S.

Bach had already mastered his profession when the opportunity to become the Leipzig

Thomaskantor arose when Johann Kuhnau died in June 1722 after having served in

the position for over twenty years. The office was (and is) filled at the

discretion of the Leipzig City Council. In this case, Bach was not their first

choice: Telemann was the preferred candidate, despite some professional

disputes with Kuhnau, but Telemann opted to remain in Hamburg. The “insider”

was Christoph Graupner (1683-1760), who had been a student of Kuhnau’s. However,

Graupner’s employer upped the ante so the prolific composer would stay with

him. That decision had long-range consequences for Graupner, restricting his

career to that of a provincial talent. Bypassed by musical history, he was left

in the shadows of Bach, Telemann, Handel, and others, despite a vast and

miraculously intact output that includes 1,400 church cantatas (“no”). Graupner’s

rejection of the Leipzig offer also forced the Council to entertain option #3,

Johann Sebastian Bach.

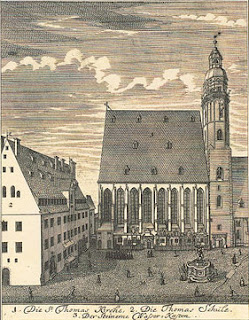

Thomaskirche and Thomasschule in Leipzig (1723)

Bach’s audition in February 1723 consisted

of leading two cantatas he had written, BWV 22 and BWV 23. The audition date

was the last Sunday before Ash Wednesday, referred to as Estomihi (from the opening

of Psalm 31 in Latin), the last performance of cantata music until Palm Sunday.

BWV 22 is believed to have been composed close to the time of performance: BWV

23 is thought to be several years earlier. So while I fleetingly toyed with

working on these cantatas together, it didn’t make sense from a compositional

standpoint.

The first movement of BWV 22 is a cleverly assembled demonstration

of useful cantata-writing skills. After a short introductory sinfonia and a brief tenor line (in a

future context this would be recitative for an Evangelist), the bass sings the

scripture from Luke as the vox Christi.

This florid arioso was perfectly intelligible to the Leipzig congregation but

still with an indication of what they would be in for eventually (e.g. the

dissonance in M.6 and M.34 and the inherent dramatic potential of the repeated

phrase wir gehn hinauf). The movement

concludes with a brief fugal coro

intended for soloist/ripienist arrangement – an amazingly inciteful

interpretation of the text about the disciples not comprehending Jesus’ foretelling

of the events of Holy Week. As the voices are added, the confusion grows – it’s

a masterful presentation of fugue and counterpoint in a tiny package. Also

instructive is that Bach chose to use only two verses of the Biblical passage –

the actual prophecies of Christ’s trial, scourging, and death are omitted. A

lesser composer would have put it all in, sacrificing focus and concision while

attempting to set a weighty text that intuitively would require music out of

proportion to the rest of the verses.

An intriguing question is how or if this

movement may represent Bach’s ideas for a St.

Luke Passion. (The composition by that name that exists in clear copy made

by J.S. and was assigned BWV 246 is not by the master.) The St. Matthew

and St. John Passions are extant, and

reputedly portions of a St. Mark, but

of St. Luke – if indeed there ever

was one – not a trace, except perhaps this movement.

An unknown poet provided

the balance of the cantata text, which is thematically tied together by the

idea of the believer being pulled or drawn (ziehen)

after Christ, and understanding what the disciples did not. The alto aria, although

probably not good recital or service material, provides an excellent study in

phrasing and breath control, particularly the last page, beginning M.62 with

some challenging intervals that cross the middle break in the voice as well as

an extended expressive passage on [ɑ] (first part of the diphthong in Leiden).

A long bass recitative begins

with a figuration on laufen,

characterizing how quickly the speaker will follow Jesus when called. Within

the context of this movement, Bach serves notice that he will be providing

drama along with worship, providing an interpretative range that can be heard

in comparing various recordings of this work. The recitative concludes with an accompagnato melisma on Freuden that leads into a gracious dal segno tenor aria. With the exception

of a tricky passage in M.105-106, this is not a difficult piece for either

singer or audience and could be a nice selection for recital or for use in

church at Lent.

Both the tenor aria and the final chorale speak of the death of

the spirit, figuratively the “killing” of the sinful part of human nature to

allow the good to flourish. Speaking of metaphorical death – poor Hubert Parry

must have come close in the service of Bach scholarship – several places in his

book reveal that he was not overly fond of the oboe (referred to in the best

tradition of “British French” as the hautboy) that of necessity appears so

prevalently in the cantatas. There is much use of the oboe in BWV 22, including

the obbligato part in the alto aria. In

the concluding chorale movement, the prominence of the oboe caused Parry to

opine:

“The

effect of a figure of the kind persisting without break or variety is often

liable to become tedious, and in this case the situation is accentuated by the

perpetual motion being maintained by the hautboy, whose poignant tones when

long reiterated produce an effect of weariness, which in extreme cases amounts

to physical distress.”

I’m guessing that the

oboe playing Sir Hubert usually heard was not at the level of the English

Baroque Soloists!

The last movement where this perpetual motion occurs is a

departure in format from other Leipzig chorale movements. A flowing

instrumental line introduces and then is interspersed with the verses of the

chorale. Commentators mention that the accompaniment was intended to reference

Kuhnau’s style. For this chorale, Bach uses a famous tune with text by Elizabeth

Cruciger, the first female poet and hymnist of the Reformation. The story of

the Bach cantatas, their composition as well as their scriptural and musical

origins, is generally a story of men, which is to be expected for the early 18th-century.

Cruciger, who was from the nobility and married into a family that was

prominent in the Reformation (her son succeeded Philipp Melanchthon at the

University of Wittenberg, while her daughter married Martin Luther’s son)

perhaps did not break the mold so much as get lucky when her hymn was included

in one of the first Lutheran hymn collections, the Erfuhrt Enchiridion (1524). I can’t be certain if she produced any

other texts, but this artifact survives today in the German Lutheran hymnal,

the Evangelisches Gesangbuch – an

impressive achievement nearly five hundred years later.

Bach’s audition piece

has done well in recorded performance, as Rilling, Gardiner, and the RIAS

recording under Ristenpart, featuring a very young Fischer-Dieskau, are all

worthwhile additions to a collection. The recording by the J.S. Bach-Stiftung

was overall a fine effort, representing the latest thinking in historically-informed

performance by an excellent orchestra, capable soloists and a fresh-sounding

choir. The aspect of live recording brings pros and cons – my impression is

that the fine-tuned performance was somewhat inhibited by striving for digital perfection,

with a resulting lack of individuality and spontaneity, such as appears in the

Gardiner Cantata Pilgrimage recordings. But there are always tradeoffs, and

this is a performance that easily handles repeated hearings – already the

Stiftung’s project has produced a substantial body of audio/video work that

will be a remarkable 21st-century document for the cantatas. And

with any luck I’ll get to be in the audience for one of them next year in St.

Gallen!

No comments:

Post a Comment